EXAMINATION OF

THE

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT

The function of the anterior cruciate ligament is to prevent the

tibia from sliding forward on the femur.

Three ways of assessing the anterior cruciate ligament are:

-

|

|

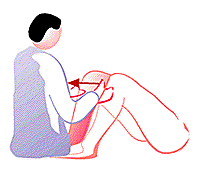

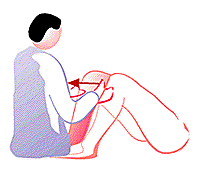

Anterior drawer

test for a ruptured

anterior cruciate ligament.

Have the supine patient flex his

hips to about 45 degrees

so his knees are at about a 90

degrees angle when his

feet are flat on the examining

table.

Sit on the patient's feet and place your hands

around

the upper part of the calf of the limb to be

examined.

Apply an increasingly firm pull on the calf.

|

|

Figure 181

|

|

-

|

|

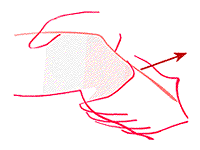

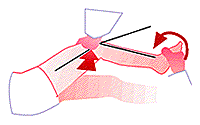

Lachman's test

for a ruptured

anterior cruciate ligament.

Passively flex the knee of the

supine patient to

between 20 degrees and 30 degrees

Hold

the lower part of the patient's thigh in one

hand and the

upper part of the patient's calf in

the other.

Pull the

tibia forward as you would in doing the

anterior drawer

test.

If the patient's thigh is too big to be held by

one

hand, stabilize the thigh by resting it on a pillow,

or

have an assistant hold the thigh with two hands

while you use

your hand or hands to pull on the tibia.

|

|

Figure 182

|

|

-

|

|

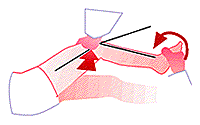

Pivot shift test

for a rupture

anterior cruciate ligament.

Have the patient lying in the

lateral decubitus

position, with the affected knee extended

and

the tibia internally rotated.

Apply a valgus stress to

the knee as you flex it.

A clunk at about 30 degrees of

flexion indicates

a positive test.

|

|

Figure 183

|

|

See (fig

181).

Have the supine patient flex his hips to about 45 degrees so his

knees are at about a 90 degrees angle when his feet are flat on the

examining table.

Sit on the

patient's feet and place your hands around the upper part of the

calf of the limb to be examined.

Instruct the

patient to relax the muscles of his legs (tight hamstrings can mask

a positive sign).

Apply an

increasingly firm pull on the upper calf.

Observe

whether the tibia pulls forward like a drawer opening up. Always

compare with the unaffected side; some normal individuals have up

to half a cm. of play in the ligaments.

If you think the patient has an anterior drawer sign, check the knee

for a sag sign. If the posterior cruciate is torn, you could be

fooled into thinking that the anterior drawer sign was present when

all you were doing was pulling the posteriorly displaced tibia back

into its normal anatomical position.

It is often impossible to hold the thigh and calf as described above

because the patient's thigh is too big for your hand. One way around

this dilemma is to support the thigh on pillows, and then use one or

two hands to move the upper tibia. Alternatively, you can get an

assistant to stabilize the lower thigh with both his hands while you

use your hand or hands to hold and pull on the upper portion of the

lower leg.

Lachman's test is more sensitive than is the anterior drawer sign.

One reason may be that it is difficult for the patient to contract

his hamstrings and thus prevent forward sliding of the tibia when the

knee is in only 20 degrees - 30 degrees of flexion. This is

particularly so if the examiner lifts the whole of the lower leg off

the examining table while performing the test.

The other situation where Lachman's test is used is during the

examination of the acutely injured knee. Often there is a

hemarthrosis and a great deal of pain. One simply can not flex the

knee more than 20 degrees or 30 degrees.

There are undoubtedly many, but I know of only one other that family

physicians should probably know about.

This is the Apley distraction test.

Have the patient lie prone on the examining table with the knees

flexed 90 degrees so the soles of the feet are facing the ceiling.

Holding the

thigh on the examining table, pull firmly upwards on the ankle or

foot thus applying a distraction force to the knee and its

ligaments, and, while doing this, internally and externally rotate

the tibia.

The idea is that such a maneuver should cause pain if the ligaments

are injured. Note that the opposite of the Apley distraction test is

the Apley compression test. The patient assumes the same position,

but the examiner applies a downward compressive and back and forth

rotary force to the knee. The idea is that this grinding pressure

will cause pain if the patient has a torn meniscus.

|

|